Laura S. Marshall <> Michael Medeiros

Poetry / Pottery / Peace

A poet approaches calm and finds focus through the practice of potteryArt and poetry are often interconnected by ekphrasis, inspiration, and expression: The visual and tactile experience of artworks can launch poets onto a river of words, and can help them see the world from new perspectives. For some poets, the tactile experience of creating visual art can spark a new way of interacting with the senses and the world. And for some, it can save their lives – and their poetry practices.

In March 2020, as universities around the world switched modes from in-person to remote, poet and potter Michael Medeiros was spinning out of control. It wasn’t only the pandemic – Medeiros’s mind had been whirling for years, thanks to ADHD and PTSD. Although he wasn’t diagnosed with either until recently, he had felt their effects for most of his life. Today, he’s making progress in fighting the whirling in his mind, thanks to mindfulness-based stress reduction training and a newfound understanding of how his brain works.

Medeiros credits one facet of his creative practice – his work in pottery – with helping to center him for the other facet, poetry. As a student in the MFA for Poets & Writers at UMass Amherst, he focused on creative writing but also took ceramics classes every semester.

He and Laura S. Marshall, who entered the UMass MFA program a year after Medeiros, sat down in March 2022 to reminisce about “poetry horns,” a pottery-and-poetry project Medeiros undertook as part of a UMass workshop they both attended with CA Conrad during the spring 2020 semester. Their conversation covered poetry and pottery, mindfulness training, pandemic isolation and poetic inspiration, clay and human connection.

LM: Tell me, how did you get into poetry?

MM: The poetry goes back forever. That goes back to childhood. But it intensified again when I started working at [the] Emily Dickinson [Museum]. About a year before I started at Emily's, I was at Northampton Poetry. It was this weekly gathering at a couple of different joints in Northampton. It was a really great crew, and it got me back into the creative writing stuff.

And then, at Emily Dickinson’s, we started the Poetry Festival, and the connections between all those different groups that I'd gotten to know over the past year, and more, dating back – it just kind of built from there. And then I realized I wanted to start writing my own, even more seriously than I had, because I'd never done the English major thing. I'd been a history major, but I was a library freak. It wasn't really a direct path – it was a circuitous route.

LM: And pottery? How did you get into that?

MM: The pottery came a few – like, five – years ago. That was when I started throwing because I wanted to know how to throw flowerpots. From there it just kind of grew.

As a kid, I'd go over to Sturbridge Village, that historical site [in Massachusetts], and they had a potter there. They actually had a historic pottery building from the 1800s, one of the only remaining ones from a New England country pottery, that belonged to a Connecticut potter named Hervey Brooks. And you’d go there, and they used to have locally dug clay: these big piles of grey clay that in the kiln would turn terracotta red. And so I’d play with that. I’d always bring some home, but I never realized that that grey clay was terracotta until I started throwing.

Most people don't want you to play with terracotta, because it's different than what most studios use – it fires differently and stuff – but luckily I ended up in Northampton Pottery, first with this guy Frank Edge, who owned it. Then he sold it to Kris O’Neill, and Kris was the savior: Kris let me bring the terracotta in.

And that was when everything was starting to collapse – I didn't know what was going on, but it's when the ADHD and PTSD stuff was making writing impossible. My entire life had been writing: I was full-time [in the Communications Office] at Hampshire College, and part-time at the Emily Dickinson Museum. But the words that just used to flow on deadline were gone. And so I think, with the clay, I was turning to something that I could do.

There was something soothing about being on the wheel. At that time, it was one of the only places that felt soothing. I had no clue why I couldn't do these things that used to be so easy anymore. Trying to learn how to center the clay, trying to make these little flowerpots – it was an alternative. It was a creative output that made me not feel horrible anymore.

I was still working at Emily Dickinson’s, but at Hampshire – I just couldn't do it anymore. So I was over at the pottery place and I would just be taking classes and learning how to make clay work for me.

This love – that's just like the writing. And as the writing is starting to come back, you know, slowly and hopefully surely, the mix of the two of them – that's my conduit of creative output.

LM: So, where does the UMass MFA come in?

MM: I'd gotten to know Dara [Barrois/Dixon] through the poetry festival over the years. And I was an older student, so I asked her, “Hey, do you think somebody like me could enter a program like this?” and Dara was so supportive of that.

That three-year window was a major life-churn time, you know. It came at the right time. even though at times it was horrible, because of what was going on with my brain. But that supportive crew – and to be immersed in something that I loved – was a magic thing. But at the same time it was bouncing off the horror of uncertainty – what the internal churn was doing.

LM: That's a really great phrase for it: the internal churn. Can you talk a little more about that?

MM: I just didn't know how to slow what was happening at that time. The first couple semesters were amongst the worst, because I didn't know what was happening. I was trying to battle through it, and it was getting worse and worse. The ability to string together sentences – to create this complex universe of creative writing – wasn't coming together the way I needed it to.

And it was extending to all different facets of my life.

Clay became this one thing I was glomming onto as a life preserver, really, amidst that scary time. Because to be in an MFA program, and people are coming in there at the top of the game – they're able to critique the work and speak to why they're doing what they're doing. Their knowledge of the contemporary creative writing world is so deep. And I'd be sitting in a corner and I couldn't put two thoughts together, and it would freak the shit out of them. And I just felt like such a poseur at times.

And then when I was trying to do managing editor work at jubilat, it was even worse, because like that required an executive-functioning brain to put everything together, and that part of my brain was gone at that time. It was just toast.

I was doing everything I could to try to pull it together. And I didn't know how, but I did know that when I sat at that pottery wheel, then things eventually would slow down enough that it started feeling like some sort of clarity again.

So I was able to do poetry, but not to the degree that I necessarily later could. By the end of the MFA I was able to get back into it, but it was there. It was there, but it wasn't firing great, you know what I mean? But fortunately I did make use of that time, to dive deep. And my connections with certain people led me to do more digging into what was going on with me.

Our semester with CAConrad was when I made the big breakthrough.

LM: So, what drew you to CA’s workshop, and was it what you imagined or expected?

MM: I think we both got nailed with this perfect storm for where we were. I don't know if you feel that same way, but it just was the perfect workshop for that time, because CA brings so much understanding and compassion and deep poetic knowledge in a way that's different from so many others. In one of the first classes we had, CA said, “So many people come out of an MFA and they're just burned out and they're not writing anymore.” So that whole course was all about making sure you retain your creative kick. It was so refreshing.

LM: How would you describe what we did? I was there, of course, but for anyone outside of that workshop …

MM: That workshop eventually led me to a deeper understanding of the mindfulness classes that I'm taking now. It really was about grounding yourself in a very particular situation, no matter where you were. That place was going to influence whatever came out of you, whatever you're writing that day. And that's so dope, the way CA does that, by creating those rituals that guide their practice. It's really about making every moment as unique as possible, in terms of both living and the creative process. You know, I love that.

I don't know if it was spoken in class, or if it was in a magazine article I read, with an interview with CA about how their family had worked in the factories, and their lives were mostly living in the past or thinking about the future, and it was never in the present. So these rituals were grounding CA in the present moment, whatever the hell that was. That was so dope.

And we did it in the class. I mean, you had to be very open to this class if you were going to take it. We had to trust one another for these rituals: to surround one another and hold each other up and whisper in their ear and tell them secret special words, and go on the elevator and mumble to one another and bump into each other. Sneaking into the showers in the basement of South College and turning on the water and scaring the support staff, going out to put our hands on the tree and receiving the vibes of the tree.

That was the most tangible class that I think we could possibly have had, prior to the final half of the [Spring 2020] semester that was the most virtual we could possibly have.

LM: Yeah, it was a huge shift. We went from very in-person and very grounded to very virtual. We also connected through shared rituals, and the communal experience of building individual, personal rituals for each other.

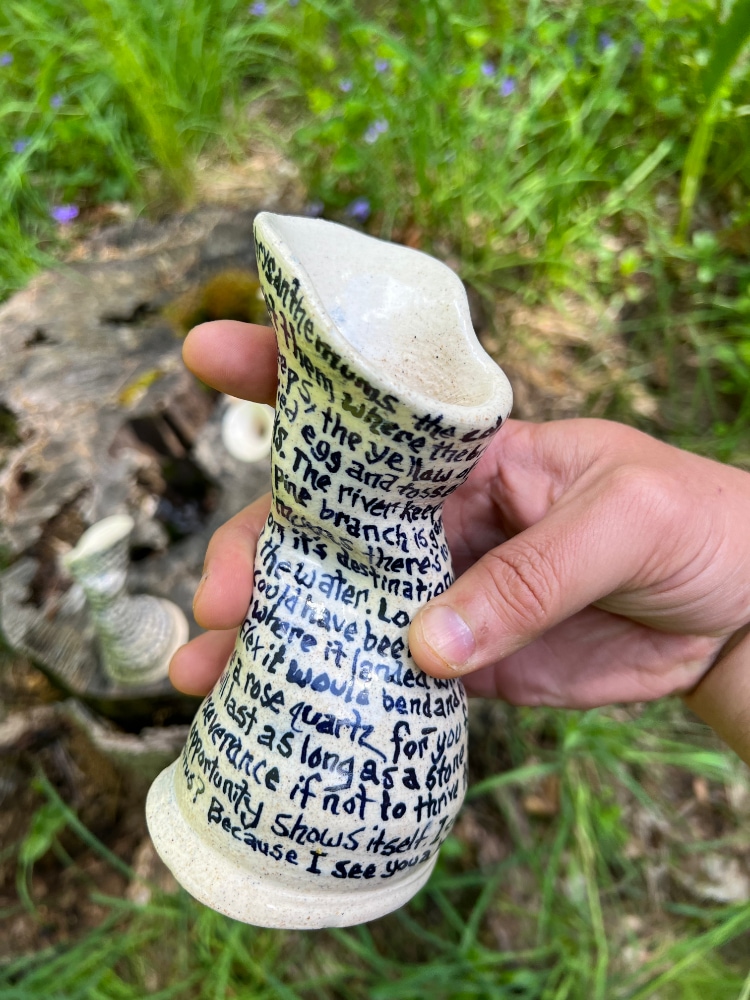

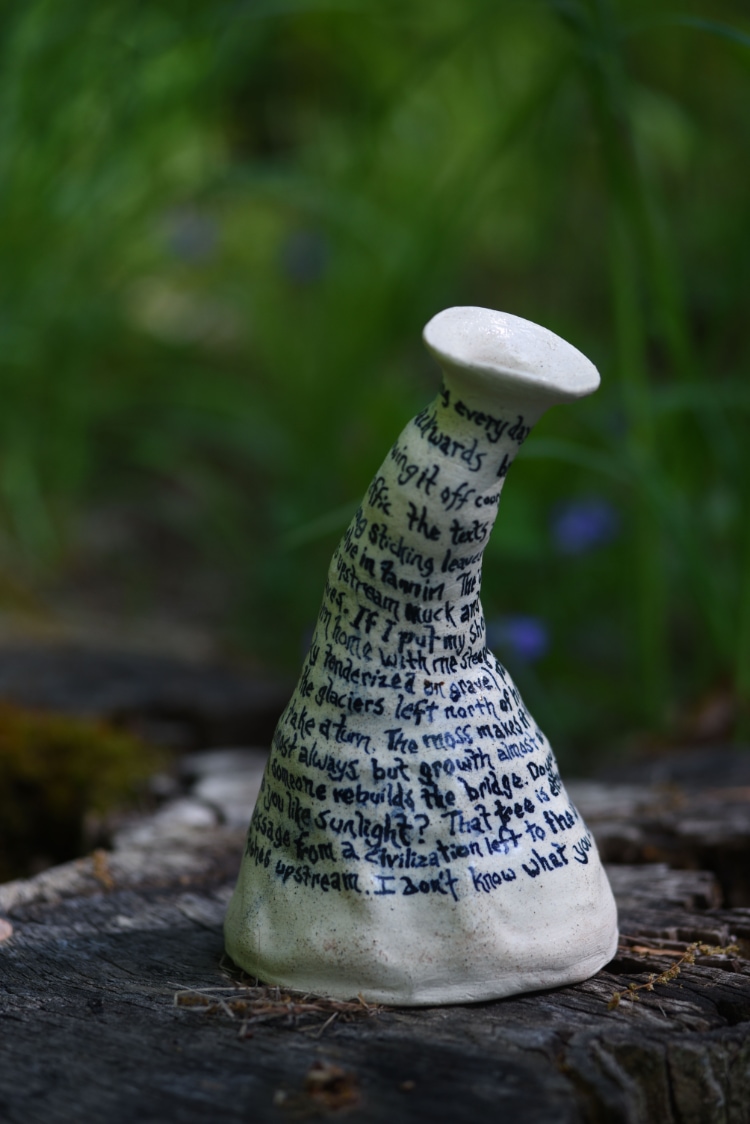

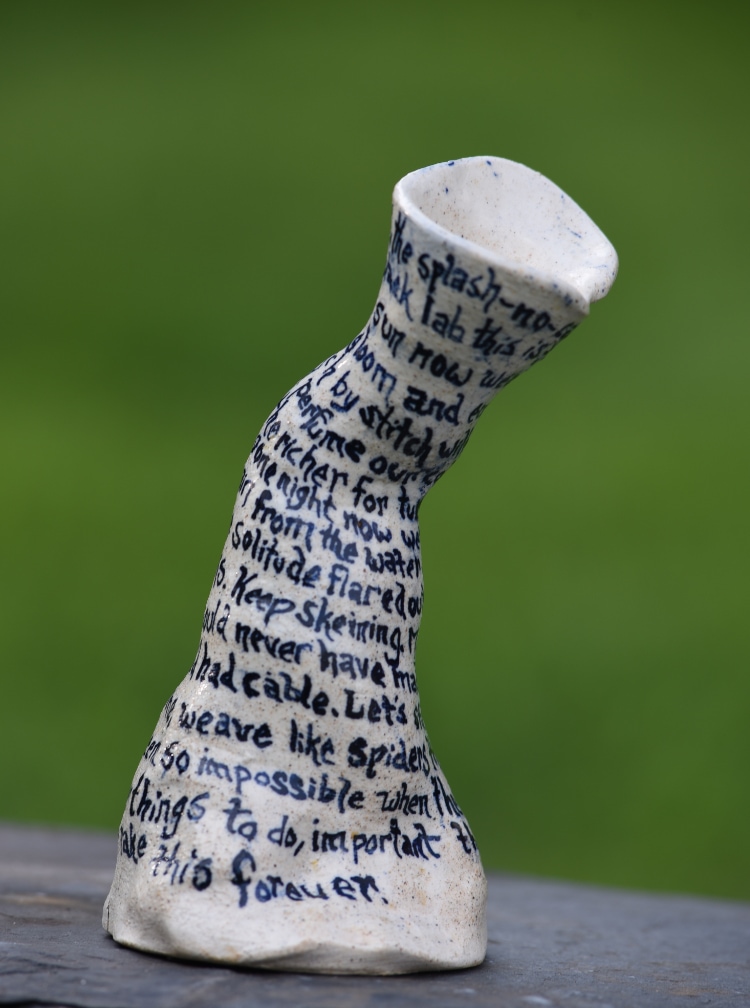

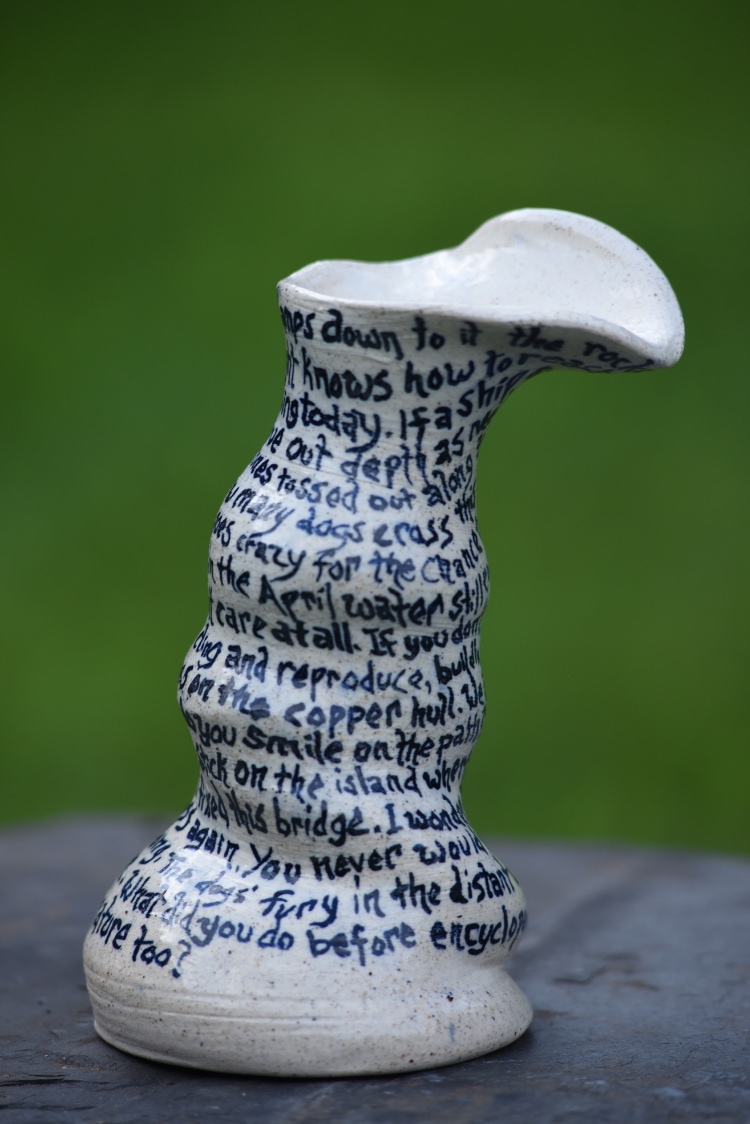

MM: In one shared ritual, we were asked to remember the first word that came into our head when we woke up every morning. So I asked each one of you if you would be willing to give me one of your morning words, and speak it through one of the ceramic horns I’d made, so that I could listen to it. And then I wrote it on your horn in black walnut ink that I’d made from the black walnut tree outside South College at UMass. That was just so I could preserve the word on the horn. And then I was planning to write poems based on that seemingly normal semester.

I think that was one of the last in-person classes before covid, maybe the last class. And so I was left with this pile of ceramic horns and no classmates.

LM: How would you describe the poetry horns? Is that what they’re called?

MM Yeah, I don’t think they have a particular name. They’re little poetry horns. That project was a very instinctual thing that riffed off of what CA was saying about creating new listening cones. A lot of people say they look Seussian. It was about creating this thing that people could speak into, and about how people could speak to me. It really evolved once the covid hit – I thought, “I didn’t know exactly where these will go. We’ve got time; we’ve got a whole semester.” And then we were separated.

LM: Process-wise, how was making the horns different from making a standard pot?

MM: I started them in a very similar way, so there is that centric draw that I have to do. I’d start off with a cylinder, and then I just kind of let my hands move it, and I was literally pulling it almost like in one of those old movies where you're changing the railway tracks. So I was really physically manhandling that, but gently manhandling it? I was really bringing my fingers into it and making the swirls and adjusting the rim so that it would have something that seemed to want to connect to a human. A human listening apparatus. I started off very off centered, and then it just moved into whatever organic form it wanted to take.

LM: How does it alter what you hear through it, because they each have their own very unique shape?

MM: It's like listening to a different shell on the shore. Every one of them brings its own sound, always a little bit different, you know, and everything has its pitch, and the amount of air that can move through it, and so each one of them just has its own little personality. Just like our classmates.

That whole workshop experience – it really was one of the most special moments of the MFA. That's something that will stick with all of us, I think, because of where we were. We’ll always be like, “I was in this workshop when everything closed down.”

LM: What became of the horns?

MM Well, you know how lonely it felt at the beginning of that thing. It was so creeptastic. Sitting around with the horns, I thought, “Maybe I'll create a ritual that keeps me in touch with these really important people in my life,” because you know these ties that we’d built up, it was really special. And it was extremely sad to be separated at a time like that, especially being an older student – I hadn't had that academic connection to people, that immersive connection, in such a long time, and then to lose that immediately, it was a stab to the gut. I didn't want it to go away. I hated it. I was like, “I don't know what to do.”

But I lived right down the street from Amethyst Brook, a little nature trail, and I thought, “What if I take one of these horns with me into the woods?”

Here's another important thing: Our classmate David Greenspan had given us these little notebooks right before the classes broke up to quarantine. They were sweet little notebooks, and each one of them had a different animal on it. I thought, “This was such a kind gift. I'm going to take this notebook, and I'm going to go into the woods looking like a total dork with my freakin’ ceramic horn and my little notebook in a plastic bag, and I'm going to go sit at the same tree.” There was this tree that was perfect for sitting against – I've always had my necessary trees to sit and read and write – and this was one of them. It was right where the Amethyst Brook ran by.

I would go sit there and I doled out four pages every morning to that particular word and that clay horn and I would just write. It was very much an immersive piece, and it tied in to the river and to those people, and to conversations we'd had and things that I remembered. It was just a very personal way to be with those people when I couldn't be with those people.

And the ceramic horn ran parallel to the poetry work I was doing. The ceramics work was just as important. Being in that ceramics studio – it was a life preserver. That was still a really major thing for me to have, that space, and the people were very cool. I learned a ton from both the students and the faculty there.

So to have both of those things together in the woods made it feel – I can't say less lonely, but – a little more connected, through those creative works.

LM: And what became of the poems you wrote in those sessions in the woods with the horns?

MM: All of them ended up in my thesis. That was a big chunk of my thesis: a section called “This River of Time and Its Creatures.” It was kind of an interlude, like a breakout thing. I stole the title from an Emerson quote.

LM: How did your approach to your brain change after your diagnosis of PTSD and ADHD?

MM: It was useful to hear that what I was going through wasn't a unique thing. To no longer feel like it was an excuse.

That was the thing that I think infuriated some of the people who are involved with me, because they’d see me not being able to get that work done, but then my dumb ass is in the pottery studio for like six hours, throwing pots. Like, “You can throw the pots, but you can't get this work done?” And it was hard to explain that the only thing that was keeping me level was spinning that fucking clay on that little wheel and making little things. There was something soothing about centering that clay.

Now it makes a lot of sense to me, because a lot of this is coming into a center. Not to be hoofty-floofty, like I said, but it's a very serious thing. A mind that's flowing well, that isn't reacting to things that aren’t there, has the ability to calmly create. It's like that big blob of clay that you fling on the wheel. It wants to go in a bunch of directions; it's got some chunky areas; it's messy. But as you learn to bring that into a whirl where a lot of evenness is happening, where that thing is compressed and ready to rock and roll – you can make some beautiful things.

At the same time, you can make some beautiful things out of the disastrous, uncentered clay, too: You can throw that thing on the wheel and just go wild. But there's something about that evenness that allows it to survive stronger. You know, it does have better strength that will survive the fire. For the longest time, I couldn't take the fire. I was just uneven, and when the heat came, I would crack.

LM: How would you say poetry and pottery are similar or different, for you, as creative practices?

MM: I'm a very instinctual creator, for better or worse, and I'm trying to shift to a more forebrain-powered approach. Like literally shifting to a more executive-functioning kind of approach, without hopefully losing that instinctual vibe. I've never been able to plan out anything; it's always come through either “whoosh, there is is,” or, it's not there, so I'll just be throwing on the wheel, making shapes, and all of a sudden, something will hit and I think, “Wait. How do we run with that? What are we going to do here? Maybe we can go here?” And then it's just this flood. Whereas I wouldn’t have the ability to just draw it out, like, “Hmm, interesting.”

I know a lot of people in the program can take poems and chop them up and work through things with the edits. That's never worked for me. It just has to be: All of a sudden this line will come and I have to get it as it comes. And it's the same thing with the clay.

I'm trying to adapt that, though, so that that's not the final result. Because, you know, the more I went through the program, the more I realized that was a bullshit approach, for that to be the finalized piece, you know, but my mind was so fast that I couldn't stay with it in a perceptive, conscious way to make any changes.

And it was around CA's class, around covid time, that I just started finally finding a way to slow enough so that I could pay attention to those lines.

Afterwards, you know, I was avoiding people so I was going to Amethyst Brook to do the writing. I also love going up to the top of Mount Norwottuck, just hiking up there every day, and I have this little lookout spot that I love, looking over the whole valley. And I would just sit there and breathe. And I’ve always done that – when I worked at Hampshire College, I would ditch out at lunch and climb up there, just so I could calm myself enough to write the rest of the day.

But this was different. One day I was up there and all of a sudden I realized, “Wait. You're not trying to slow down the outside world – your inside is going so fast, and that's what needs to be slowed down.” It was this aha moment, after these decades of trying to figure it out.

LM: That must have been exhilarating.

MM: Did I tell you about undergrad at UMass, when I was in my dorm room? I was sitting there in my chair just kicking back one day, and all of a sudden a calm came over me, and this clarity.

I was doing this 1000-words-of-typing-a-day, but it was just frenetic, not particularly useful – I mean, it led me to being a better writer but it was also led me into bad habits. It wasn't the greatest approach, but it just hit me and I was like, “Whoa,” and everything there was so clear, and I'm writing and I'm seeing things slow. And I ran to my buddy’s room and said, “Dude, I think I figured it out.” I was referring to my constant attempt to really hone my creative focus. And of course I bombed down there and it was gone, because I'd gone back to my old habits.

But that was the moment when I figured out I needed to slow. Still, it would be years before I would understand how. It was only around the time of our CA workshop when I really gained an understanding. I was having these moments where I was starting to feel that moment of clarity again. It was in a controlled way, not very long. I'd work on trying to slow down, and I had maybe a couple seconds of that “Ooh, cool.” And I just kept working on that. It was in the connections with a couple of people who were having some challenges themselves that led me to start to do some reading as well.

And that led me to the ADHD stuff and the PTSD from growing up in New Bedford – you know, it wasn't the worst place, but I was shot out several times, and a lot of my friends were getting into big fights, and there was always a threat. I didn't realize I was always on guard, and it started to make sense to me that those moments of slow were when those defenses were dying down, when I was going back to like a body at rest, at calm.

And it was really hard to get there, but I kept trying to figure out how to slow down. Every day I spent a good amount of time on it, to the point where I was having some conscious success. So the next year, I went for an assessment, mostly to see whether or not I was deluding myself. And they said, “Yes, this is what's going on, and what you're doing [with mindfulness] does seem to make sense, so keep trying. And if it doesn't work, you can try medications as well.”

Once I got the news from the experts, I thought, “Fuck this, I'm going right in,” so that whole final semester I spent about 10 hours a day trying to figure out how to slow it. And it paid off, man. I'm starting to get to the point where, if I can't control it every day, at least I understand where I am.

And clay and the poems, and all those moments, the CA class – all those things tied in so deeply to bringing me to a place where I know the importance of grounding in the moment. I know that the mindfulness shit sounds so vague at times, but it's a very specific thing for me. I feel like certain areas of my brain, when I'm able to slow that threat area, that fight-or-flight – and I am flight, a hundred percent flight and freeze .

I remember being in Peter Gizzi’s class in the second semester and during office hours he asked me, “Who are your favorite poets?” And I completely froze. My brain was like, “We're not gonna say any words now. We're done. Just talk about chocolate or something.” And I felt so embarrassed for the next two and a half years. Because I have so many poetry loves, and I couldn’t express that.

So that final semester, when there was an opportunity to take Peter’s class again, I said, “I want to see if I've learned anything. I want to see if I’ve made any progress, so that I can actually talk intelligently with somebody who has such a deep love for teaching and for the poems and for all that stuff.” I wanted to be able to see if I could hold my own there, because I felt like shit that I couldn't that first time.

And in that last semester, even though it was in fits and spurts – it wasn't perfect – I was able to talk about these things again, and I was able to write more deeply. I was able to take my poems and think through them, not just have them come out and then have such a whir that I wouldn’t be able to go back to that creative space and edit. That was magic. And a lot of that concrete success started in CA’s class, with those horns and everything. Those moments.

Or maybe I'm just like Emily Dickinson. I need my solitude in order to figure shit out. But the Peter class was a really magic way to end the MFA.

LM: It sounds like everything came together in a new way for you.

MM: When I was preparing my thesis. I went back to look at the poetry collection I'd written to get in. And it was horrifying, you know, because it was all this very rough stuff that just came out. Most of it was written in a one-month burst. I was writing a poem a day, and I thought it was the greatest shit. But looking back I was like, “Wow, no.” It was interesting, some of it, but it was also just thrown out and there was no going back to sit with it. There was no figuring out what was the point of every word and line. I think that's one of the most valuable things that came from the MFA.

Another was seeing the different techniques and everything – that hit me, both in the poetry workshop and in the clay studio. I wouldn't have made those horns if I hadn't had a professor, Cynthia Consentino, who was always pushing me, asking, “Why do you keep making pots? It's so boring.” Like, I love pots! But to really think outside, and to be exposed to what my classmates were doing with different writing on things, and the design work, more abstract work – I love both. I'll take whatever people can throw at me, and I won't necessarily make anything that's related to their stuff, but it will affect me, and then send me off on a different little twirl.

Do you remember the conversation in CA’s class about clay absorbing sound and how that would change it, in whatever minute way? It would change the constitution of that clay. It would forever affect what would be in there. I love that.

When you guys spoke your words through those horns – it was very important to have that done, so when I’d take them into the woods, those words had been spoken through every horn, so all those people had their hands, their human selves, somehow connected to that.

MARCH 25

(DAVID—FLOAT)

Single pine branch broken in the river

by the broken bridge. We only

float so far before getting

caught up on the rocks, the

sand bar, a root.

Been here with loves and I’m

here today, run drunk

from someone I didn’t

love through the woods

and back alone.

The water falls further on. I can

hear it going downwards and over.

Another bridge up-brook to cross

if needed. The rain’s coming.

Patches of

snow on the dirt and moss.

A circle of

Salem moss left to the Amherst woods

like jumper cables.

My father’s lens captures

everything I focus close upon

and the things out of focus too.

No clay to build with here but

broken saplings, a dog or two distant.

A waterfall forms where the fallen

tree jammed the debris. How many

years it’s been filling like a dirty porcelain tub,

a tidepool calm.

Dogs furious back by the roadway.

I haven’t seen a thing float by but

I know that’s the tendency.

MARCH 28

(MARCELLA—WHEN)

Put the dog on a fucking leash

if he’s that big and gonna

growl. The end times don’t

need canine threat. Listen

to that water run, the

falls will be pounding after

this week’s rainfall. The

gardens will be leaching

nutrients to the seed, the

cold-hardy will peek up

momentarily.

Sow the home crops and when the summer

comes we’ll be self-sufficient loners.

Did the beavers build that

or is it just natural accumulation,

chaos in a row. What do I smell,

suck up enough air and

it feels medical, alcohol-stung.

When it’s this cold in mornings still

the dew is frost on the butt of

my pants damp from sitting on

frosted leaves. They crunch like

cauliflower chips when my full

weight settles in.

When this is through I hope

they rebuild the bridge.

The leaves have gathered up

into a peak by the shore.

The train doesn’t go by

at this hour. When it does

a curdled ghost a mist of

Emily Dickinson’s father

argues a state congress for a

railway line through town.

Some people are making happy

voices in the distance. A small dog

approaches and turns back.

I prefer you to a behemoth.

Yeah man, dig down in that dirt,

rub all the stink in you can.

Scratch beneath the collar.

We’ve got a limited palette

of things to do on this planet.

We run on instinct and instinct

says I’ve seen this before but

I’ve never seen this before and if

I didn’t buy it at the flea market

this weekend god knows it

90 percent won’t be there in June.

MARCH 29

(SARAH—STITCH)

Every dog is curious.

The cannonball

dunk of the black lab.

This is the perfect

day. Forget sun now.

We’re going deep into

gloom, embroidering it

stitch by stitch

with our own stink

and perfume.

Our color scheme is all

the richer for turning

inward. Sew a veil

from the droplets, weave

a train with the water scum.

We’ll marry the solitude

flared out like albino

peacocks. Have you heard

them skeining in the distance?

My great grandmother

would never have crocheted

so many doilies

if she’d had cable.

Let’s stitch now while

we have the time, weave

like spiders the lace

patterns that seem so

impossible when there are

other places to be, other

things to be done, importance

to decide. I decided

I’ll make this forever.

MARCH 30

(JENNIFER—PARADISE)

Paradise is the

go-back knob, the fix-it-all,

the Massachusetts Lottery

machine at the Big Y,

and the Lucky 7

$5 card is gonna be

the million scratch

and if not at least

doubles on whatever

number hits.

The cannonball dog dove in again.

He’s got paradise in

every droplet on every

blade of fur dripping down.

How fucking cold is that water?

He’s in love.

If I could fall in love that hard

we’d never have a text drama again.

My floor would be spotless

for your tiny feet if I could

dive in like that dog.

MARCH 31

(JAMIE—FORKS)

Someone revived the

chrysanthemums. The

cold bath doesn’t

destroy but preserves.

Who set them there

where the brook forks,

glowing like Easter

Peeps, the yellow of

fried hard yolk plucked

and tossed to the raccoons

in the compost heap?

The river keeps running

and the broken pine

branch washed away.

But the chrysanthemums.

There’s no stopping a flower

from its destination, no

stopping a dog from the water.

Look at that pale, gnarly sycamore.

Could have been the biggest tree on

Earth but for where it landed where

the brook forks. If it could flex

it would bend to kiss the chrysanthemums

or eat them.

I’ll leave a rose quartz for you for always.

I think you in particular will last as long as a

stone. Some tender things stick around if

not to thrive then to throw down a few blooms

when the opportunity shows itself.

I can’t smell you from here.

I only taste raw garlic and the slick of

olive oil hot enough to bubble egg whites

to browning but I see you

a brook’s width away.

APRIL 1

(CA—BARNACLE)

The copper’s clean.

Not a thing clamps

down to it, the rocks

are bare of everything, the

sunlight knows how to reach

in and snatch a soul.

All the dogs are crossing

today. If a ship sailed

this brook it would

carve out depth as needed,

dogs, gravel, and stone

tossed out along the shore

in a groove.

Everyone goes crazy

for the chance to soak

their shoe-covered feet

in the April water,

still cold as snow melt.

The dogs don’t care at all.

If you don’t stay still

a barnacle can’t cling

and reproduce into a

geodesic commune on the

copper hull.

We all keep our distance now

but do you smile on the path?

What creature at night snuck

up to eat the dark bouquet?

Someone left their walking stick

at the island where the brook forks.

Still nobody’s fixed this bridge.

The dogs’ fury in the distance

makes me heave to run.

What did you do before the

encyclopedias told you

the werewolves were nature too?

Something’s peeping in the foliage,

a bird or a frog. Seems since I put the

rose quartz in the bottle the

bark of the nearby trees has

grown pinker.

APRIL 3

(JAYSON—ALONE)

Never alone even in the solitude.

Nothing gives way like the

floor you’ve overburdened,

beams rotted away below,

and the shock of falling

is nothing compared to

the landing on a cool

moss floor.

Even the daily friendliness is rebuffed.

I won’t touch the fur of even a smiling

strange dog. I won’t keep the conversation

going from three feet away. I know I’m

a weirdo in the woods. I know

conversation is at a premium.

I would hug

the world but for my

personality.

An only child plays well without others,

could burst like a supernova from your magnetic draw.

I was told not to talk to strangers young

and this is a booster shot.

I suck up the solitude of woods, do not growl

like the territorial dogs but do not wag

my ass in appreciation. I regret

being cold but I have a

quarantine to maintain and I

stopped explaining my quirks

years ago. Boy I’m a sullen

boy.

A wet log downstream rotting.

The pine trees smell like wet dog.

A wet dog arrows friendly my way

on a short-lived trajectory. The dog brain spots

something else, near instantly my

brain does the same.

Maybe on nicer

days we won’t be so alone.

Michael Medeiros is a poet and potter living in Amherst, Massachusetts. He is a graduate of the UMass Amherst MFA for Poets and Writers program, and served as managing editor of the literary magazine jubilat. A 2018 apprentice at the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works, he is the editor of the poetry compilation A Mighty Room: A Collection of Poems Written in Emily Dickinson’s Bedroom, and co-founder of the Tell It Slant Poetry Festival based at the Emily Dickinson Museum in Amherst, MA.

Medeiros recently studied Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction through UMass Worcester Medical School and is continuing his studies, hoping to become teacher-certified in the techniques. In the future, he aims to teach Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction to others, tying it into ceramics and poetry. In the meantime, he has launched a ceramics business, Poesia Pottery, based in Florence, Mass. He is working on producing ceramics for events and installations throughout New England.

Laura S. Marshall (she/they) is a poet and former linguist who lives outside of Albany, NY. Their work appears or is forthcoming in South Dakota Review, Bennington Review, juked, and elsewhere. She is a guest editor at Trestle Ties and a former special features editor for jubilat.